Manchester, Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan — Our View

Witnesses to Monday night’s horrific attack in Manchester, England, described the confusion, the smoke, the blood splattered all over the floor. After a suicide bomber detonated his device following a concert, people mentioned the empty shoes: Blasts tend to blow victims right out of their footwear.

Most of all, survivors remembered the children killed or maimed. The bomber coldly calculated that pop star Ariana Grande would draw young teenage girls, and the venue was indeed packed. An 8-year-old girl named Saffie Rose Roussos was the youngest to die.

The more than 20 deaths and dozens of hospitalizations made the Manchester attack, for which the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria has claimed responsibility, England’s worst since 2005 and the fourth deadliest in Western Europe since 2015. “We struggle to comprehend the warped and twisted mind that sees a room packed with young children … as an opportunity for carnage,” British Prime Minister Theresa May said.

Suicide bombings are among terrorists’ most insidious tactics and one for which Western nations have mostly and fortunately been spared since 9/11. They are, by contrast, a cruel fact of life in the Middle East and South Asia.

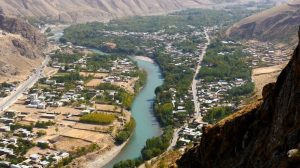

Just this year, dozens died when two suicide bombers detonated explosives near the Afghanistan parliament; at least 36 were killed when a driver exploded a bomb-laden truck in Iraq; and a suicide bomber at a Pakistan religious shrine killed 75 people.

After Manchester, there will be calls to harden “soft targets.” Bags were searched at the Manchester Arena on Monday, though witnesses say without much diligence. Even so, heightened security is an imperfect response to suicide bombers. An evil, suicidal zealot willing to sacrifice himself — or herself — in a crowded place is almost impossible to stop in real time. If denied access to a concert, there is always a bustling train station or a shopping mall.

Other reactions are worse than imperfect. People will clamor for more “extreme vetting” of immigrants. But the bomber in Manchester, identified as 22-year-old Salman Abedi, was born in that city, the child of Libyan immigrants.

So how to better defend against these attacks?

One way is to remember that citizens are on the front lines, and that their roles are essential. Before a suicide bomber straps on an explosive, there’s a troubled life that must be lived out to the point of radicalism. Friends, neighbors and relatives are the witnesses to this behavioral change and are subsequently suspicious. Only to the extent they share what they know with a trusted police department can lives be saved.

But this also cuts both ways. Law enforcement and community leaders have to make it easy for first- or second-generation immigrants to step forward with their valuable insights about people who’ve become radicalized. Inflammatory rhetoric about banning all Muslims, or labeling Islam a hateful religion, only makes this more difficult.

Even with the right intelligence, law enforcement needs the resources to monitor threats. This was difficult in Britain. The Economist reported the domestic intelligence service knew of 3,000 potential extremists, but only had the manpower to monitor about 40 at a time.

As we’ve said after previous terror attacks, the war against violent Islamist extremism is not one that will be over soon. It can’t be won by playing defense or “containing” the threat. The international community must take the fight to ISIS, which has established strongholds in Syria and Iraq.

Yet even as a U.S.-led coalition closes in on Raqqa in Syria, the de facto capital of ISIS, the kind of twisted ideology that motivated the Manchester attack will continue to fester in the shadows and erupt in places as joyful and innocent as a pop star’s performance.