Afghan parents in desperate poverty often rely on sending children to work, but a school run on donations offers young people an alternative to a life of toil.

In a large house in southern Kabul, Abdul Baqi Samandar has built simple classrooms and workshops for street children.

Omid used to spend his days in traffic jams around Kabul, washing cars with a ragged cloth. At the end of the day, the seven-year-old took home the money he had earned so his father wouldn’t sell another piece of furniture from the house to buy drugs.

Haroon began working in traffic at the age of six, as an espandi, warding off evil spirits by waving a tin of coals over car bonnets so smoke wafted through drivers’ windows. On his best day of business, a woman in an armoured vehicle rolled down her window and handed him 1,000 afghanis (£11). On most days, he earned less than 100 afghanis.

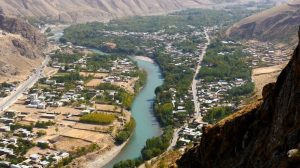

Kabul, one of the world’s fastest growing cities, is in the throes of a rapacious urbanization. The majority of residents live in slum-like squalor. For the parents of Omid and Haroon – as for thousands of others in the Afghan capital – relying on their children was a means to cope with poverty.

Unlike many of their peers in the streets, however, Omid and Haroon have been given a second chance at childhood. At a large house in the south of the city, they now study during the day with dozens of other children, practising martial arts and learning life skills such as cooking and wood carving in several classrooms and workshops.

In one room, a row of girls sit at wooden looms, weaving rugs. The sound of girls practising the alphabet emanates from the room next door. In the underground gym, boys and girls do martial arts together. Every day about 150 children come to the school, says founder Abdul Baqi Samandar, who employs 25 teachers.

It might not sound like a hard sell, but Samandar says he often finds it difficult to convince parents to let him give their children free food and schooling to keep them off the street.

“I tell them, ‘Your kid has the right to study. Why must your kid stay in the street for one piece of bread?’” Samandar says.

Children learn woodcarving, among other activities, at the school founded by Abdul Baqi Samandar in Kabul.

Samandar says he receives no funding from the government or foreign NGOs. Instead, his school runs on donations from friends abroad – he lived for many years in Germany – and from local patrons, such as print shops, which donate discarded paper.

A 60-something social activist and former journalist, Samandar says the number of children hawking in Kabul’s streets has grown visibly over the past decade.

The Afghan president, Ashraf Ghani, has made urban planning and housing reform a main priority, but has failed to resurrect the economy, after the withdrawal of most foreign forces in 2014, and the collapse of many development projects.

Nevertheless, in Afghanistan cities are seen not just as places of opportunity but of safety. Over the past year, the capital has come under further pressure from the forced expulsion of more than 600,000 Afghans from Pakistan, and a record number of Afghans displaced by the intensifying conflict.

After the civil war that claimed 250,000 lives ended with last year’s accord, Lucy Lamble investigates how Colombia’s communities plan to build lasting peace.

“Children are very quickly sent out to beg in the street,” says Nicolle Hervé, co-director of Samuel Hall, a thinktank that has just completed a study on Afghan children who work on the streets – some of whom still attend school for part of the day.

“Parents, unless they are educated themselves, do not see why there would be a contradiction between work and school. Children can beg for 10 hours and go to school for five,” Hervé says. “But even if they do, it’s uncertain what they get out of it because of psychosocial traumas and the capacity to get something out of school.”

Harroon, now 13, says: “Before, I didn’t understand anything in school. Now I learn much faster.”

Kabul’s population has quadrupled since 2001 to an estimated 6 million people. Afghanistan’s urban population is expected to further double within 15 years. In Kabul, just under three in four people live in informal housing (pdf).

In the Khair Khana neighbourhood, on the slopes of a mountain next to rows of Soviet-era apartment blocks, about 900 Kuchi families have settled in ramshackle brick houses.

For centuries, Kuchis pursued a migratory lifestyle, but this has become increasingly threatened by war. The families in Khair Khana moved to Kabul from Laghman 15 years ago. As they were pushed out by fighting, their animals were killed or snatched by either government forces or the Taliban, says Emam, a community elder.

‘We’re the sons of Afghanistan, but our leaders have forgotten about us’

A few years ago, the government asked Kuchi families in the Kabul neighbourhoods of Khushal Khan and Parwan-e Do, to move to Khair Khana to make space for new housing.

“They promised us electricity and water. They gave sweets to the people,” says Emam.

Not only did the government not deliver on its promises; two years ago, police tried to evict the Kuchis from Khair Khana, laying siege to the area for 20 days. Armed with sticks and rocks, the Kuchis managed to push back the police. Since then, they have built their own houses and wells, but have yet to receive government assistance.

“We would prefer to live in the desert, but we can’t make any money there,” said Emam.

Omid, now 11, also uprooted his life when he came to Samandar’s house. His mother, Fazela, had fled her drug-addicted husband with her children, and the family now life in an annex on Samandar’s roof.

Fazela’s children started working as soon as they were old enough to sell empty plastic bags on the streets because her husband was incapacitated by drugs and was unemployable. “We had no other choice,” she says.

Children take part in activities at the school in southern Kabul. Photograph: Sune Engel Rasmussen for the Guardian

Compared with the children who beg or toil in the streets, Afghan women are less visible casualties of urban poverty. In rural areas, some women are able to contribute to their family’s income, for example by helping out during the harvest, but in the city many find it harder to make a contribution.

“When the same women end up in urban settlement,” says Hervé, “they often can’t go out any more. They cannot contribute to the household income.” If their husbands can’t find work, tension in the home escalates and often results in domestic violence, he says.

Omid’s oldest sister, Sadaf, 19, is studying for her university entrance exam. This is her final attempt to go to university, after her father forbade her to do so last year. That is another reason Fazela left her husband; to give her daughter the chance of a good education. “I don’t want her to have the same life as me,” says Fazela.

Guardian