China has started the process of extending the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to Afghanistan, and then stretching it to the country’s other neighbors in the Middle East and Central Asian nations as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Analysts say China’s economic goals including accessing the vast potential for minerals in Afghanistan, and to be in a position to reap rewards from the reconstruction of the war-torn country once the process begins.

“China can expect a lot of economic benefits by investing in Afghanistan. Such investments will strengthen Chinese projects in Pakistan, and also help China to access natural resources in Afghanistan. Afghanistan also has the abundant potential of hydroelectricity, which Chinese companies can tap and sell in Pakistan,” Ahmed Bilal Khalil, a researcher at the Center for Strategic and Regional Studies in Kabul, tells The National.

CPEC is one of the six economic corridors in China’s hugely ambitious BRI, which aims to link infrastructure across Asia, the Middle East and Europe, and use these facilities to build and connect industrial zones. Others include the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor and the New Eurasian Land Bridge connecting China to Turkey and other parts of Europe.

Beijing also plans a China-Central Asia-Western Asia Corridor enhancing China’s links with the Middle East and Turkey and the China-Indochina Peninsula covering Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Others are the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Corridor (BCIM).

Some parts of South East Asia already have fairly well developed connectivity, including a major road starting from Kunming in China that runs into Vietnam and Laos. But BCIM may be difficult to implement because India is reluctant to join the Belt and Road programme as it maintains one of its components, CPEC, is violating Indian sovereignty by passing through the disputed region of Kashmir. Myanmar, meanwhile, supports some parts of Chinese investments but it has blocked others including a US$3 billion hydroelectricity dam that China wants to build and send the electricity generated across the border for its own needs.

China is already considering a set of six projects that can be implemented by extending CPEC to Afghanistan. These projects include the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan energy transmission line and a motorway or rail connection from Peshawar in Pakistan to Kunduz in Afghanistan and possibly into Central Asia. A motorway project between Peshawar and Kabul is also on the cards and there is also the possibility of building a road link between Torkham and Kabul to join an existing road with Pakistan. Railway lines already under consideration include one linking Pakistan’s Landi-Kotal with Afghanistan’s Jalalabad, and another from Pakistan’s Chaman to Afghanistan’s Speen Boldak, Mr Khalil says.

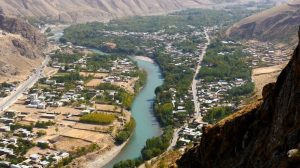

A huge hydroelectricity project to produce 2,800 megawatts on the Kunar River has been under discussion for a long time. But implementing this project is not straightforward because there is no water sharing treaty between the two countries, Mr Khalil says.

M K Bhadrakumar, an author and former Indian diplomat, can see why China is interested in Afghanistan. “One trillion dollars worth of mineral resources are available in Afghanistan. Extending the BRI to Afghanistan will facilitate extraction of the minerals to the Chinese economy. It will also facilitate export of China’s industrial surplus to Afghanistan.”

But David Kelly, the director of geopolitics at the Beijing-based consulting firm, China Policy, says investing in Afghanistan is fraught with risks that include fears of project disruptions by the Taliban.

“We have been told by diplomats and knowledgeable sources that there are fierce competition and differences between different regions of Afghanistan,” he tells The National. “Building in one region might result in opposition from another region. China is accustomed to negotiating with a central authority … It is not comfortable in places like Afghanistan where there is no central authority.”

Meanwhile, the Chinese railway equipment manufacturer CRRC Tangshan announced yesterday that it has delivered 19 subway trains with 95 subway carriages to Turkey’s port city of Izmir. Each subway train has a maximum capacity of 1,286 passengers.

Analysts say China’s economic goals including accessing the vast potential for minerals in Afghanistan, and to be in a position to reap rewards from the reconstruction of the war-torn country once the process begins.

“China can expect a lot of economic benefits by investing in Afghanistan. Such investments will strengthen Chinese projects in Pakistan, and also help China to access natural resources in Afghanistan. Afghanistan also has the abundant potential of hydroelectricity, which Chinese companies can tap and sell in Pakistan,” Ahmed Bilal Khalil, a researcher at the Center for Strategic and Regional Studies in Kabul, tells The National.

CPEC is one of the six economic corridors in China’s hugely ambitious BRI, which aims to link infrastructure across Asia, the Middle East and Europe, and use these facilities to build and connect industrial zones. Others include the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor and the New Eurasian Land Bridge connecting China to Turkey and other parts of Europe.

Beijing also plans a China-Central Asia-Western Asia Corridor enhancing China’s links with the Middle East and Turkey and the China-Indochina Peninsula covering Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Others are the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Corridor (BCIM).

Some parts of South East Asia already have fairly well developed connectivity, including a major road starting from Kunming in China that runs into Vietnam and Laos. But BCIM may be difficult to implement because India is reluctant to join the Belt and Road programme as it maintains one of its components, CPEC, is violating Indian sovereignty by passing through the disputed region of Kashmir. Myanmar, meanwhile, supports some parts of Chinese investments but it has blocked others including a US$3 billion hydroelectricity dam that China wants to build and send the electricity generated across the border for its own needs.

China is already considering a set of six projects that can be implemented by extending CPEC to Afghanistan. These projects include the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan energy transmission line and a motorway or rail connection from Peshawar in Pakistan to Kunduz in Afghanistan and possibly into Central Asia. A motorway project between Peshawar and Kabul is also on the cards and there is also the possibility of building a road link between Torkham and Kabul to join an existing road with Pakistan. Railway lines already under consideration include one linking Pakistan’s Landi-Kotal with Afghanistan’s Jalalabad, and another from Pakistan’s Chaman to Afghanistan’s Speen Boldak, Mr Khalil says.

A huge hydroelectricity project to produce 2,800 megawatts on the Kunar River has been under discussion for a long time. But implementing this project is not straightforward because there is no water sharing treaty between the two countries, Mr Khalil says.

M K Bhadrakumar, an author and former Indian diplomat, can see why China is interested in Afghanistan. “One trillion dollars worth of mineral resources are available in Afghanistan. Extending the BRI to Afghanistan will facilitate extraction of the minerals to the Chinese economy. It will also facilitate export of China’s industrial surplus to Afghanistan.”

But David Kelly, the director of geopolitics at the Beijing-based consulting firm, China Policy, says investing in Afghanistan is fraught with risks that include fears of project disruptions by the Taliban.

“We have been told by diplomats and knowledgeable sources that there are fierce competition and differences between different regions of Afghanistan,” he tells The National. “Building in one region might result in opposition from another region. China is accustomed to negotiating with a central authority … It is not comfortable in places like Afghanistan where there is no central authority.”

Meanwhile, the Chinese railway equipment manufacturer CRRC Tangshan announced yesterday that it has delivered 19 subway trains with 95 subway carriages to Turkey’s port city of Izmir. Each subway train has a maximum capacity of 1,286 passengers.